Artists and Illustrators Magazine June 1993

Emily Patrick’s approach to painting is exemplary; one gets the impression that more painters desrve to come to their profession the way she has, with no formal art training, but with a fascination for art history from an early age. Looking at original work, talking to established painters and devloping the skill of looking, is the course she has followed in order to produce honest renditions of the people and things around her which provide her with beauty and security.

She has come a long way from taking a list of necessary items for painting from Sir William Coldstream.Impressionists and spontaneity and warmth, her inspiration was originally fired by the Flemish, jewel-like paintings of Van Eyck and Hans Memling and the cleanness of the colours. Now she paints like a virtuoso from a more reverent age and although her paintings ooze the freshness of the 19th century. She was also impressed by the austere classicism of Masaccio and the abstract qualities of other early renaissance masters. Even now she eschews the moderns, preferring Vermeer and Degas. She realises she is on her own in terms of contemporary art practice, which she considers superficial: exciting for its audacity, but severely limited in its appeal.

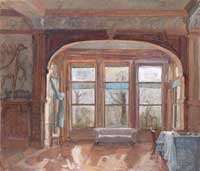

Meeting her at home is like stepping into one of her own painted panels. A large, open room with a high ceiling, carved wooden alcoves and panelling, polished floorboards, old Regency-style sofas, a glass-fronted cabinet full of jugs, cups and saucers, and vast amounts of southern light, make her working environment. This she transcribes variously and exquisitely into oil. She prefers to paint at home, finding studios “…very dead places”, whereas here she is looking around for pictures the whole time.

The constant chatter of her inquisitive daughters in the next room complements the various portraits of them. One - particularly memorable - is Mother with a Red Hat, a bold composition of the painter and her younger daughter, Isabel, who is slumped against her mother’s free arm, lost in the bliss of sleep. The dusty-blue of the sky spills onto the rich frame which, not untypically, is crucial to the work and made by the artist and her husband. Like the other paintings this has tremendous charm but not at the expense of strength. It is a classical subject shot through with the intensity of the artist’s gaze. It is also an intriguing picture-within-a-picture, reiterating powerful statements of universal maternity and of her own creative roles as both mother and artist. The painter has been compared to Mary Cassatt but for me Patrick looks further inside to trace the move of individual sitters, rather than to offer more general sentiments.

The artist executes her paintings with immense skill. Flowers are rarely painted well; they can be messy, or fussy, or both. Yet Patrick tackles these difficult subjects in a uniquely successful way, managing to portray the essence of their exuberant yet fragile nature. Modestly, she puts this ability down to bravery and determination. The apparent ease with which she executes her paintings belies an intuitive but disciplined approach to balancing composition.

If at any time she feels in fear of losing control, she submits to a different force, allowin the painting itself to take over. She is selective about what she paints, feeling that it is unnecessary to paint things that are ornamental without being functional. Similarly she resists restating in paint a picturesque or dramatic landscape because both lack subtlety. She prefers a hedge and a tree in one field, perhaps, and cool, consistent light, even to the extent of being drab or grey. By contrast she likes harsh light for still lifes and finds that the timescale involved in capturing fleeting effects adds to the adrenalin. She describes capturing this in a practical way, “I choose the direction in which a painting will go because I am chasing a particular magic which I have seen; a different style wouldn’t get that magic”. It is clear that her love of colour is at the root of each picture she makes. She rarely worries about her palette becoming muddy or unmanageable because she insures that the pigments she uses are, not surprisingly, “all very beautiful”. Emily Patrick, 1992

Emily Patrick, 1992 2 St Johns Park

2 St Johns Park Mother with a red hat

Mother with a red hat Cherries Gooseberries

Cherries Gooseberries The Thames Estuary

The Thames Estuary